Drug and Device Development: Balancing Benefit and Risk – A Regulatory Framework by Janet Woodcock, M.D.

Archival Context: This article reconstructs the seminal insights presented by Dr. Janet Woodcock, Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the FDA, during the 2016 Cardiac Safety Research Consortium (CSRC) proceedings. The presentation, titled “Drug and Device Development: Balancing Benefit and Risk,” outlined the FDA’s strategic shift towards a structured, qualitative framework for decision-making, with a specific emphasis on incorporating patient experience data into the regulatory review process.

Executive Summary

The approval of a new medical product involves a complex calculus. It is rarely a binary choice between “safe” and “unsafe.” Rather, it is a probabilistic assessment of whether the potential benefits to a specific patient population outweigh the potential risks. In 2016, Dr. Janet Woodcock articulated a transformative vision for the FDA: moving from an implicit, internal judgment process to a transparent, structured Benefit-Risk Framework.

This framework is particularly critical for rare diseases and conditions with high unmet medical needs, where patients may be willing to accept higher uncertainty or safety risks. As referenced in Advances in Therapy, integrating patient and caregiver perceptions into this calculus is no longer optional—it is a regulatory mandate.

However, the “Risk” side of the equation begins long before a clinical trial enrolls its first patient. Dr. Woodcock’s framework implies that rigorous pre-clinical safety profiling—utilizing high-purity chemical probes and toxicity screening libraries—is the foundational layer upon which all subsequent risk-benefit decisions are built.

The Structured Benefit-Risk Framework

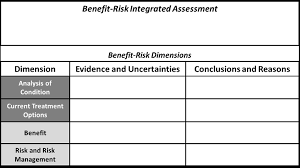

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that the “Benefit-Risk” assessment is not a mathematical formula but a qualitative judgment informed by quantitative data. To standardize this, the FDA implemented a five-part grid that guides reviewers through the decision-making process.

The first step is establishing the context. How severe is the disease? Is it acute or chronic?

- Regulatory View: For life-threatening conditions (e.g., metastatic oncology or advanced heart failure), the tolerance for adverse events is higher.

- Research Implication: Understanding the pathophysiology of the condition requires robust basic science. Researchers utilizing kinase inhibitors or signal transduction modulators to map disease pathways provide the biological rationale that justifies the development program.

How well are patients served by existing therapies?

- If a population has no approved therapies (common in rare diseases), the FDA may accept a novel agent with a significant toxicity profile, provided the benefit is demonstrable.

This is the domain of clinical trials. Does the drug work?

- Evidence: Derived from randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

- Endpoints: Survival, functional improvement, or validated surrogate endpoints.

Safety is the most complex variable. Risk is not just the presence of side effects; it is their frequency, severity, reversibility, and manageability.

- Mechanism-Based Toxicity: Many adverse events are “on-target” effects. For example, a potent VEGF inhibitor designed to starve a tumor may inevitably cause hypertension or proteinuria.

- Off-Target Toxicity: Unintended binding to other receptors (e.g., hERG channel blockage causing arrhythmia).

[INSERT IMAGE HERE: FDA Benefit-Risk Framework Grid] (Instructions: Insert a standard table or graphic of the “FDA Benefit-Risk Framework” grid. It typically has 5 rows: Analysis of Condition, Current Options, Benefit, Risk, Risk Management. You can create a simple HTML table or find a generic image of this framework.)

- Caption: Figure 1. The FDA’s Structured Benefit-Risk Framework. This matrix guides reviewers in weighing the clinical evidence against the severity of the disease and the availability of other therapies.

Risk Management

Can the risks be mitigated?

- REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies): Restricted distribution, patient monitoring protocols.

- Labeling: Boxed warnings.

Patient Experience Data – The New Frontier

Note: This section directly addresses the “referring page” context from the Springer/Advances in Therapy article regarding patient perception.

One of the most significant pivots discussed by Dr. Woodcock in 2016 was the formal inclusion of Patient Experience Data (PED). Historically, “Benefit” was defined by clinicians. The 21st Century Cures Act and PDUFA V initiatives pushed for the patient’s voice to define what constitutes a meaningful benefit.

Why Perception Matters

In rare disease trials, a statistical improvement in a biomarker might not translate to a feeling of wellness. Conversely, a small functional gain (e.g., being able to hold a cup) might be invaluable to a patient, even if it falls short of primary endpoints.

- Methodology: The FDA encourages the use of Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and qualitative interviews.

- Relevance to Discovery: When developing drugs for niche indications, researchers often start with target validation using small molecule inhibitors in phenotypic assays. Understanding the patient’s phenotype helps guide which molecular targets (and thus, which chemical tools) are prioritized in the discovery phase.

The Foundation of Risk Assessment – Pre-Clinical Toxicology

Note: This is the strategic “Bridge Section” connecting the FDA regulatory topic to Selleckchem’s product lines (Inhibitors/Libraries).

While Dr. Woodcock’s presentation focused on the clinical and regulatory adjudication of risk, she acknowledged that the “Risk” profile is largely inherited from the molecule’s chemical properties. The predictability of clinical safety relies heavily on the quality of early-stage discovery toxicology.

Defining the Safety Margin

Before a Benefit-Risk assessment can occur in humans, a “Safety Margin” must be established in the lab. This involves:

- Target Selectivity Profiling: Ensuring the drug candidate hits the intended target (e.g., a specific kinase) without inhibiting critical safety targets (e.g., cardiac ion channels).

- Metabolic Stability: Determining how long the drug stays in the body.

The Role of Reference Libraries in Safety Screening

To predict clinical risk, developers use annotated compound libraries—collections of known drugs and toxins—to benchmark their new molecules.

- Cardiotoxicity Screening: New candidates are screened against hERG, Nav1.5, and CaV1.2 channels. Validating these assays requires high-purity ion channel inhibitors (such as Dofetilide or Verapamil) as positive controls.

- Hepatotoxicity Screening: Liver injury is a leading cause of drug withdrawal. Researchers use cytotoxicity libraries and reference hepatotoxins to calibrate their in vitro models.

- Figure 2. The Safety Pharmacology “Funnel.” Regulatory risk assessment begins with robust in vitro profiling. Researchers utilize comprehensive chemical libraries to screen for off-target activities (e.g., kinase selectivity, ion channel inhibition) before clinical development.

Translating Safety Signals to Clinical Monitoring

Dr. Woodcock noted that uncertainty is the enemy of approval. When a safety signal emerges (e.g., a slight increase in liver enzymes in Phase II), regulators must decide: Is this a trend or noise?

Biomarkers as Decision Tools

To reduce uncertainty, the FDA advocates for the use of Safety Biomarkers.

- Cardiac Safety: Moving beyond QT interval to biomarkers of injury (Troponin, FABP3).

- Renal Safety: Novel biomarkers like KIM-1 or NGAL.

Scientific Validation: The validation of these biomarkers depends on chemical biology tools. Researchers use specific inhibitors to induce toxicity in controlled cellular models, verifying that the biomarker rises in response to the specific insult. For instance, using a Cisplatin reference standard to induce renal damage in a model system to test the sensitivity of a new kidney injury biomarker.

[INSERT IMAGE HERE: Chemical Structure of a Reference Standard] (Instructions: Go to Selleckchem and download the structure of a classic “Reference Compound” used in safety, such as Terfenadine (hERG toxicity reference) or Acetaminophen (Liver toxicity reference).)

- Alt Text:

Chemical structure of Terfenadine, a reference compound for cardiotoxicity screening - Caption: Figure 3. Chemical structure of Terfenadine. Once a marketed antihistamine, it is now a standard reference compound used in cardiotoxicity assays to test hERG channel liability, illustrating how withdrawn drugs become vital tools for safety screening.

Benefit-Risk in the Era of Precision Medicine

The future of the Benefit-Risk framework, as envisioned in 2016 and realized today, lies in Precision Medicine.

- Stratification: If a drug has a high risk, can we identify the 10% of patients who will respond so well that the risk is worth it?

- Companion Diagnostics: Identifying genetic mutations (e.g., BRCA, EGFR) that predict response.

This precision approach drives the demand for highly selective small molecule inhibitors. A “dirty” drug with broad kinase inhibition might have an unacceptable Benefit-Risk profile. However, a selective inhibitor designed to target only the mutant protein might offer a pristine safety profile. This necessitates the use of High-Throughput Screening (HTS) libraries during discovery to find that “magic bullet” with the perfect selectivity score.

Conclusion

Dr. Janet Woodcock’s presentation serves as a foundational text for understanding modern drug regulation. It reminds us that “Balancing Benefit and Risk” is not a static event at the time of approval, but a lifecycle process.

For the pharmaceutical scientist, the takeaway is clear: Regulatory success is built on pre-clinical rigor. The ability to present a favorable Benefit-Risk profile to the FDA depends on the data generated years earlier at the bench—using reliable chemical probes, precise analytical standards, and comprehensive safety screening assays to characterize the molecule’s true nature.

As patient voices become louder in the regulatory process, the demand for drugs that are not just “statistically significant” but “meaningfully beneficial” will only grow, placing an even higher premium on the precision tools used in early discovery.

References

- Woodcock, J. “Drug and Device Development: Balancing Benefit and Risk.” CSRC Annual Meeting Presentation, 2016.

- FDA. “Benefit-Risk Assessment in Drug Regulatory Decision-Making.” Draft Guidance for Industry, 2023.

- The Case for the Use of Patient and Caregiver Perception of Change Assessments in Rare Disease Clinical Trials. Advances in Therapy, 2019.

- PDUFA V: Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.